[Read the first of Suzi Steffen's reviews from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival here.]

My Fair Lady, Oregon Shakespeare Festival artistic director Bill Rauch told the media at a press conference, is only on the schedule this year because of director Amanda Dehnert's passion for the project. Rauch—who loves the American musical, in general, deeply, and who brought The Music Man to the Bowmer at the beginning of his tenure a few years ago—explained that figuring out the season is a massive undertaking.

With the help of a system called the Boar's Head, he and up to 50 (that's right, five zero) other people figure out which Shakespeare plays to schedule and then start putting new plays, commissioned works in the American Revolutions cycle, musicals, and beloved other plays into the season planning (right now, the 2014 season is set, and they're gently starting the planning for 2015).

But, Rauch said, some productions get on that 11-play list purely because of a director's passion. Last year's marvelously messy Medea/Macbeth/Cinderella was his own passion project, and this year's is Dehnert’s vision of My Fair Lady.

The musical came out on Broadway in 1956 and as a movie in 1964 starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison. Theater kids and adult fans probably know every word of the movie, even the annoying words, even the classist and sexist abuse Professor Henry Higgins heaps on the Cockney and other poor street folk he happens by one night in the Edwardian era.

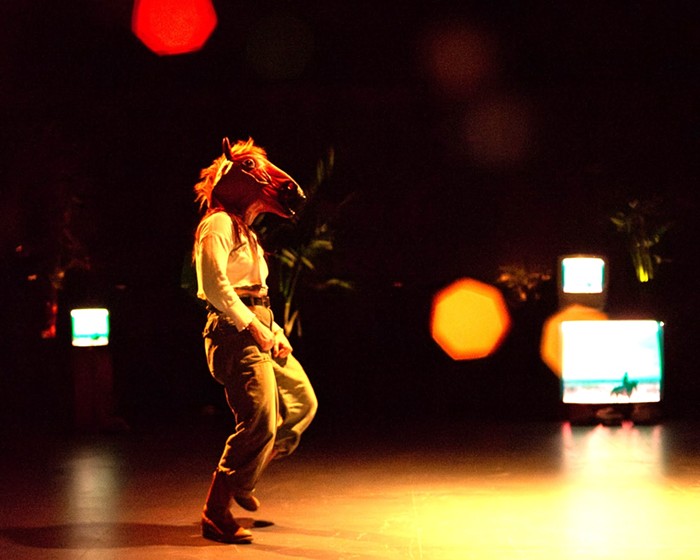

In the OSF version, company regular Jonathan Haugen plays Higgins, and newcomer Rachael Warren is Eliza Doolittle, the Cockney flower-seller who sees that she might be able to make something of herself if she can just change the way she speaks. Dehnert's vision is something like the recent Anna Karenina movie—the musical takes place within a theater, and the audience witnesses some of the costumes and costume changes.

Many people love My Fair Lady, love every Lerner and Loewe song from "Why Can't the English Teach Their Children How to Speak" to the undeniably catchy "I Could Have Danced All Night." The whole musical tilts toward the ridiculous given that it's filled with U.S. actors trying to sound like English people who are trying to sound like other English people, and the class issues just aren’t funny, but what the hell, the music (delivered by two wonderful piano players and a couple of violinists who also act and dance and sing in the ensemble) is fun.

Warren's singing voice fills the Bowmer nicely, but it’s Haugen who fires up the stage in his scenes as the fussy, snotty "confirmed bachelor" (and definite asshole) Higgins. You might want to present the eleventyzillion household servants with some Karl Marx and the knowledge that WWI is about to change everything, but that's just social realism rearing its Les Miz & Downton Abbey-tinged head—and this is not a realist kind of experience.

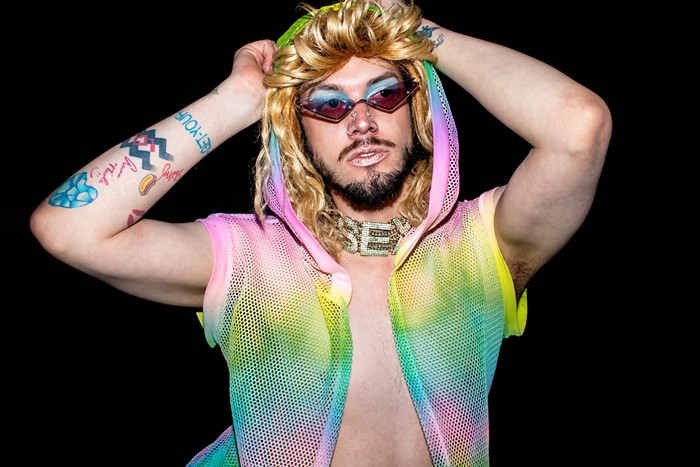

The most surreal thing about it might be Anthony Heald, who played Shylock in Merchant of Venice in 2010 and Duke Vincentio in Measure for Measure in 2011 (not to mention his screen career: Silence of the Lambs, Boston Public, Boston Legal, etc.). Heald plays Eliza's dad, the reprobate Alfred P. Doolittle, a comic figure who sings "With a Little Bit of Luck" and "Get Me to the Church on Time." Heald dances, mugs, and generally looks both a bit winded and fully exhilarated by the experience. He’d probably steal the show if his scenes weren’t entirely separated (except for one) from those with Eliza and Higgins.

Heald and Haugen (a strong duo in 2010's Equivocation) make the entire regrettable storyline almost worthwhile, and a self-mockingly silly company march to the footlights at the end signals Dehnert's wry wink to the ambiguous and problematic final few lines.

A fellow audience member we talked to at intermission wasn’t thrilled with what he called the “fluffiness” of the musical—it wasn’t worthy of the OSF, in his opinion, despite the excellent acting, singing, and dancing. He was much happier with what we’d seen earlier in the day: August Wilson's Two Trains Running.

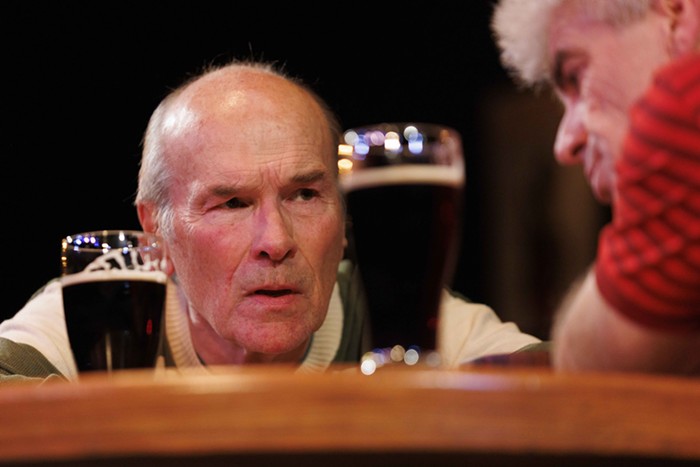

Two Trains, set in 1969 in a fading diner in Pittsburgh and first produced in 1992, is part of Wilson’s 10-play cycle about African-American life in the 20th century. This piece nearly turns into a meditation on the art of the monologue, at least in the first act. The characters—especially the diner’s owner, Memphis (Terry Bellamy); a numbers runner, Wolf (Kenajuan Bentley); Memphis’ old friend Holloway (Josiah Phillips); and a young man just out of prison (Kevin Kenerly)— talk at and past each other, rarely interacting much more than they need to in order to get to the next speech.

Not that what they’re revealing is boring. Their life stories include the Great Migration and a varied analysis of economics, jobs, eminent domain, and choices—but not in a school lecture way. And when the men do get a little bit blowhardy, Risa (Bakesta King)—the slowest, most resistant server in the world—will shuffle over with coffee, or the local crazy guy, Hambone (Tyrone Wilson) will come in yelling. Everyone except maybe Wolf has in some way been done wrong by others, and they’re telling those stories to rebuild their lives or figure out a way to solve the harms of the past.

The mosaic pieces of this story of the Steel Belt turning slowly to Rust fit together better after intermission, when the pressures on Stirling to find a job, on Memphis to figure out how much money he can get from the city to sell his building, on Wolf to deal with Stirling’s intensity, and on Risa to figure out how to get what she wants, rise high enough that the play moves toward action. But action isn’t precisely the goal of Two Trains. With Aunt Ester—a mystical figure who tells African Americans what to do when they need advice, requiring only that they put money in the river to pay her—hovering offstage and Holloway dispensing short pieces of survival wisdom and commentary, Two Trains offers an opportunity to consider the arc of these characters’ lives. Where that arc touches history and community, sparks might fly, but the play’s surprising final 20 minutes seem to claim—that arc will indeed bend toward justice.

For tickets and show details, head to osfashland.org.