- photographs by denis c. theriault

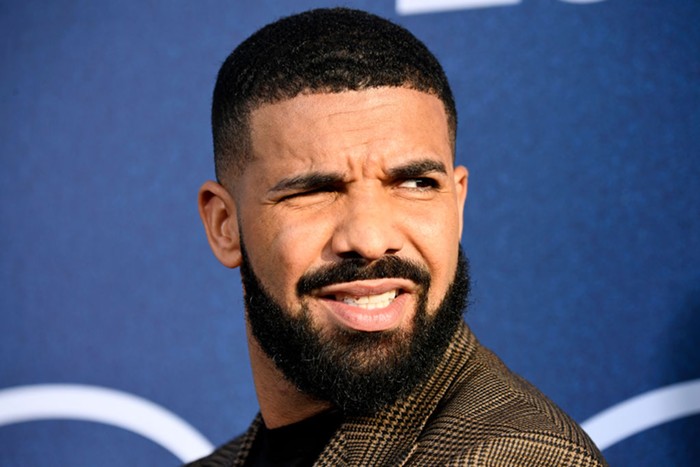

- Daryl Turner, left, says hello to Mayor Charlie Hales before this morning's forum at NE Portland's Bethel AME Church.

But that's not precisely why today's hours-long forum, organized by Teressa Raiford, is interesting.

Joining Hales is Portland Police Association president Daryl Turner, who reflected on the murder of two New York cops last month with a long statement complaining about nationwide protests fomenting a culture of hatred against cops. After that speech went public, first reported by the Portland Tribune, protesters planned a rally at PPA headquarters but held a chat with Turner instead.

Hales' office is also taking time to talk about federal police reforms and ongoing oversight efforts, chiefly an entreaty to put in for a Community Oversight Advisory Board. The deadline for that board had been Friday. But it's been extended one more week, until next Friday, January 16.

Dozens of people are here—including retired state Supreme Court Justice Paul DeMuniz, who's been selected as the local face of a Chicago team of academics hired as the compliance officer/community liaison team for federal police reforms.

First to give substantive remarks is Hales' public safety advisor, Deanna Wesson-Mitchell. Wesson-Mitchell, who grew up on Northeast Portland, opened with remarks about how she got to be a police officer—a job she made clear to say she quit after 10 years before joining the mayor's office.

She's got a colorful story. She's talking about growing up as bi-racial, and learning about the need for social justice as a kid or university student. Her dad is a former Black Panther. The family once lived next to Hell's Angels who kept a pet lion.

She grew up not liking the police. But then she decided, with her sister, to join the bureau after attempting other careers, in part to serve the public. During her time in the bureau, she was one of the officers devoted to working on equity issues for the inside, she said.

"Portland is a very white city and people don't like to talk about race," says Wesson-Mitchell. "Trying to get people to talk about race is one of the things in the police bureau where we've made a lot of progress over the years."

Among the reforms she's also touting? A new test with better questions for officer hiring—something that requires input.

11:05

Hales is talking now. He's glad for the chance to come here to talk.

"The police bureau in Portland is a work in progress," he says. "But there's been progress."

He says community relationships are his top priority as police commissioner. He's talking up the federal reforms. He's also calling controversy over the city's clarifying appeal of a judge's order for regular updates on the reforms "a legal sideshow." He says he expects mediation to settle that next month.

Hales is also talking up his choice of police chief, Larry O'Dea (read our long conversation with O'Dea, which was published just this week). And he says the walking beats the bureau began on SE Hawthorne, where cops had been dealing with homeless youth and others, could be a model for Portland.

And now he's mentioned his willingness, first reported by the Mercury, to invest in a long-delayed drop-off/crisis center for people experiencing mental illness. He says that need flared anew after the Labor Day shooting, on Interstate 84, of DeNorris McClendon, who'd been in an emergency room the night before his shooting, only to leave, and now in the criminal justice system.

"This is a big deal," Hales says.

On the subject of body cameras, he says efforts to obtain them have been put on hold while the city works on legislation in Salem to balance privacy with the public's right to know what its police officers are doing.

11:13

Turner's explaining that if his voice breaks or cracks, he's just getting over a terrible cold.

"The police union is not the enemy," Turner says. "We want to be part of that progress. We need to part of the conversation that educates the community."

He's blaming the media who "obviously have an agenda." He says he's been a cop for 24 years, raised in poor in New Jersey—so poor you couldn't buy new shoes in your size. "I didn't come from a silver spoon."

He talks about seeing riots in New Jersey, knowing that cops there brutalized a black taxi driver, starting that. He didn't want to be a cop, he says, when he first was approached. He liked the job he had. He didn't trust the police. He eventually took the test and says he's learned otherwise. He hopes community members visit the bureau's new training facility to get a sense of how and why cops do the things they do.

If people do that, he says, "maybe you'll get a better understanding" of why cops react in certain situations.

Turner's remembering his time in the 1990s doing gang enforcement. He's noting the changes in Northeast Portland over the years. And he's not certain disparities in traffic stop and search data can be fully explained, but he's hoping to learn something from the community.

He also says the PPA doesn't condone racism or sexism. "By any means or any form."

Turner says regular conversations must continue, so people feel comfortable talking to him about problems with officers, so he can maybe mediate those discussions. He says Raiford "can call me 24/7."

Raiford says these meetings, by the way, don't mean the community will stop protesting. "We're turning up," she says, to applause. "Education is everything."

11:23

The first question is about cultural competency.

Hales says diversity hiring is "foundational." He says over the past two years, 42 percent of new recruits have been either women or people of color. "Let's keep doing that recruitment after recruitment after recruitment," he says, hoping more people of color decide to sign up to be "a change agent" for the burea from the inside.

Second, Hales says, is "how we train" officers. When the cops added a job back last year, it was an equity manager whose office will sit next to O'Dea's. O'Dea has told me that person will craft the last phase of racism/bias training for the bureau—for the hundreds of rank-and-file cops who have yet to go through a course that's been tailored for commanders and sergeants.

Wesson-Mitchell is talking more about that training. In 2012, 62 command staffers went through that training. Then the sergeants went through in 2013. But it was driven by volunteers—and the job of translating it for the duties of street cops and specialty units meant the city needed to hire that new person. That person's close to being hired, going through background checks. (Wesson-Mitchell used the "she" pronoun when talking about the hire.) The training's supposed to happen this year.

She's also talking about the COAB and how it will offer "additional voices" that command staff ought to consider and consult when crafting new policies. Sometimes, she says, the cops think a policy they've spent time on is great and are stunned to learn the community has issues with it. Getting that input earlier, she says, may avoid that. That kind of conversation might also keep cops in management from staying within something that's super easy in Portland: residing within a "white experience."

Portland also "needs people from the community to apply and become police officers," she says.

11:28

Raiford says Don't Shoot Portland supports getting involved with some of these community oversight opportunities.

Turner wants to weigh in, saying the city's bureau is one of the nation's best. "But we can always be better." He says it'd help if cops got better at why they're stopping people or talking to them, particularly when encountering different cultures.

He says he even "struggles" sometimes as a black man at places like Fred Meyer, where maybe he'll be asked about his rewards card and a white patron wouldn't. Explaining traffic stops, he said, would help. Maybe you're getting off without a ticket for a busted tail light because it's your first time being pulled over.

But we're not "over-policed," he says, citing statistics showing Portland smaller per capita than Seattle. "If your cities are safe, businesses will come here, with jobs for people of color, jobs for women, jobs for everybody."

Of course, he's also talking about how livable and nationally notably safe we already are.

Raiford says her definition of "over-policing" is different. It doesn't mean how many cops we have. It means her brother not being able to drive his Cadillac, because three out of five days he'll be pulled over down the block. Along with an over-representation of African American men in places like Busted magazine, notorious for printing local mugshots.

11:42

Raiford makes clear "we haven't been protesting without dialog." She says the groups have been holding weekly education forums since August, well before the protests heated up over the fall. "We're very well informed" about whom to consult with issues.

"The protest is to make sure people know we're not being pacified and that we're still out here," she says.

Dan Sandini, a conservative blogger and filmer, questions some of the protest chants. "All the cops in the ground," he says. "NOT US," the audience says. Another one was "Deck the halls with piles of dead cops." He also cites the case of the white kid who stood up on police cruiser, demands a denunciation. And also says people on Facebook celebrated the shootings of the New York cops. He was booed and hissed.

Raiford says she doesn't expect people to jump into their protests and says organizers have been focused on safety.

Glenn Waco says "that's a public Facebook page." He's up next.

He's asking Hales about equity efforts and Hales having black people working in the city, but not, Waco says, in the police bureau. Waco then asks about why 86 cops came out to the McClendon situation. And he asked about body cameras and wants Hales to speak again about why the city's waiting to obtain them.

Hales says he won't apologize for sending cops to a report of a guy with a gun on a freeway. Turner says that was most of the cops on shift that day.

Hales thanked Turner for not fighting his efforts on body cameras and says he believes the city council has agreement on buying them. Waco says cops should have their cameras on at all times while they're on duty. Hales says that's part of the legal fight. A TV station might ask for footage of a domestic violence incident and air it. "There are boundaries we need to draw," the mayor said. "These cameras, used the right way, are a useful tool."

He says a policy on the cameras will go before the community before it's enacted. "I hope you exercise that" opportunity, Hales says.

Waco confronts Turner about his reticence to be filmed in his office, after getting Turner to say he thinks people have the right to film police.

Another speaker questions the large part of the general fund budget that goes to the police bureau.

She wonders how Turner can "sound so conciliatory today," after saying "petulant things" questioning why cops have to endure the "scrutiny of those who have never walked in our shoes?"

Hales says the police bureau has shrunk 52 or 53 positions since he's been mayor. The one added back is the equity manager. "We don't hire teachers," he says. "You can say that's good, you can say that's bad," he says, "but those are the facts."

11:45

Raiford reads from a card asking what the city's doing to give black men a second chance after getting felony raps that might make it difficult to obtain schooling and employment.

Hales touts the city's approval of "ban the box," meaning the city won't ask about convictions. Raiford says she wants to talk about going through Salem for a statewide push. Hales also wants to copy a Philadelphia program in which businesses that hire "returning citizens"—don't call them ex-convicts, he says—would receive tax credits. Hales touted the 7 percent recidivism rate for that program in Philadelphia.

"I want to cross out Philadelphia and write in Portland," he says.

11:55

A young man named Anthony Williams asks about efforts to hire more African Americans into the bureau and Hales' goal.

"My goal is a police bureau that's culturally competent and reflects the diversity of the city," Hales says, pointing out that he'll never understand what it's like to be African American. Having cops who are black "will do a better job" of understanding the city's diversity "than an all-white police bureau.

Wesson-Mitchell says the bureau is 85 percent white and 15 people of color, about "10 percent off the city's Census proportion." And the bureau's 15 percent women, Wesson-Mitchell says... but they're mostly white women. She asks if any women of color want to join up.

Another speaker, an African-American woman, questions why the bureau doesn't fire more cops who commit misconduct against people of color. She says people don't understand the rules cops apply when deciding if someone's resisting arrest or not. Then she questions the mayor's white people diversity training, led by white people—which people called "contradictory."

Hales says the city is discharging officers who break policy. Twelve police officers in the past two years have been fired or had their departures "secured." He's talking up a new discipline matrix that's helped shape discipline now. "We don't always agree with the union," he says. "But I have to give the Portland police union credit" for not fighting discipline meted out under that guideline.

Hales specifically mentioned the firing of Dane Reister, who shot and nearly killed William Kyle Monroe after mistakenly loading a live round into a beanbag shotgun.

Wesson-Mitchell defended the "White Men as Full Diversity Partners" training, saying it is possible for white men to speak to people about institutional racism. She says it's good to get "white men to see how they as white people, as men, as heterosexuals are imposing their expectations of what's normal on other people, and how to not do that." If people reviewed the training, she says, "you might like what you're seeing."

11:59

Turner is answering a question about the "military-grade" weapons people think police use.

He defends the adoption of Tasers—"they're not toys"—as a less damaging than the way cops used to handle disturbances, piling onto people five at a time.

Hales says he finds "military-style" weapons "disconcerting." And he's right that Portland doesn't quite use them like other jurisdictions. He says force during the third quarter last year was done almost two-thirds from what was reported during the same part of 2008. Hales defends Tasers as a way to avoid officer-involved shootings.

The same speaker asks about mental health training. Turner says the bureau now has a behavioral health unit. He also says cops have access to a counseling program, along with their families, if they're having mental health issues on their own.

Raiford's now cautioning people to respect the church and "be respectful."

12:08

Someone's questioned Hales' touting of improvement in traffic stop and search data. She says the gain isn't in less disparity in stops but in a reduction in disparity in the "hit rate" when cops search whites vs. African Americans and find contraband.

That's partly because of training, she says. Cops are doing less "consent searches" randomly, like when they see someone not doing something wrong at a bus stop. Hales promised to put the data on his website.

The next speaker asks about why cops who used excessive force against people of color or with mental illness are still on the force. Hales says he can't address the past. But he's working every day to impose consistent discipline now, he says.

(Hales says unanswered questions today can be sent to his office and that he'll issue answers.)

Another speaker asks again about body cameras.

Hales cautions that cameras can be used to "improve justice," but also "to make things worse." He says officers with cameras who talk to citizens are "likely to do a really good job" when having that chat. He's also hoping for an impartial record of shootings. He touts the Merle Hatch shooting, which was captured on an iPhone.

Wesson-Mitchell says we need policies for sensitive situations like when cops are talking to sex assault victims or informants, or in a mental health crisis. "That's how it can negatively impact the justice system."

Turner warns about medical privacy violations—when cops are near someone's conversation with paramedics, say. "There are a lot of legislative changes that need to be made," Turner says. "This isn't put it on, press the button, and let's go."

12:13

Former council candidate Nick Caleb wonders why we don't have a system of direct civilian oversight of the police, not having a police commissioner who's elected in charge. He asks if the city would back that, and if the PPA would back that or not.

Hales says he believes it's "my job" and that he's accountable. He also points to the Independent Police Review office, run by the auditor, as a "separation of powers." He says he doesn't know of any cities where citizens who "aren't given public authority like I am as mayor can fire public employees." He's not sure that's even a good idea, if it does exist.

Caleb asks about Captain Mark Kruger—the "Nazi" cop, someone shouts—whose discipline in 2010 for a Nazi-era shrine was scrubbed in a legal deal signed by Hales.

Turner says that's between the defunct Portland Police Commanding Officers Association and Hales. He says Hales disbanded that union maybe to have more control over his officers. He says he and Hales may not agree, but that they recognize that arbitration is the final word. (Except, under then-Mayor Sam Adams, when they challenged the reinstatement of Ron Frashour.)

12:27

Someone's reading Turner's December statement now about the murder of the two New York cops. The speaker said he started researching police unions after the meeting protesters had with Turner, saying he's noted they have a dual role—protecting cops from punishment but also advocating for working conditions.

Turner's declining to speak, saying it's a statement and not a question.

Donna Maxey just raised the notion of Raiford running for mayor, to big cheers. "I didn't say when you were making it, just to remember you when you make your next run for mayor." She's thanking the bureau and union and Hales for being willing to engage in this way, something that's clearly not been happening in other cities.

Maxey, who runs Race Talks, says white people need to go into their communities to talk about race. She says the bureau is sponsoring several public forums on race, paying for food and child care. The Albina Ministerial Alliance "is a major player in that." She also mentioned that Turner is signed up to speak.

She says she appreciates white people's support, "that's what we need, but please be sure to let the people who are suffering the most speak the loudest."

Speaker Mario Haro, who talks about his heritage as a Chicano, is accusing Turner of "kowtowing to a racist institution." He's complaining about Christianity with a white Jesus as a colonial oppressor. He's accused Hales of fascism for working through the streetcar industry after he was on council.

The pastor on the panel asks him to get to his point, after talking about the "black Jesus" on the cover of the bulletin for this event. "What's the point of respectability politics?" he says.

The pastor starts speaking... "we represent a Jesus of many colors. Jesus may not be white, may not be black, may not be red or brown... but it's to who we look at as a sure enough liberator. ... You cant assume what other people think or believe and you can't think for me or anybody else in this room.... Come up with some community action points that you can address... because you're all over the map."

Raiford says he needs to step down. "You're doing the same thing. You're dominating and using power."

12:35

The next speaker questions the grand jury process as biased and run by prosecutors. He was on a grand jury. He's been in juries where a verdict was decided on a Friday but the DA came back on a Monday and said "we need a different verdict."

"I've had this personal experience," he says.

Hales says the city doesn't run grand juries. But he says the city's insisted on public transcripts for shootings. (Just the fatal ones, I'll note.) Hales says he's not yet involved in pushing Salem to make changes on that front in Salem.

It's the last speaker before lunch, provided by Dub's. He's asking Turner about his assertion that Portland's one of the nation's safest cities—minorities don't feel safe he says. "Are you safe? Are the police safe?"

Turner says that's why he's here. He's talking again about the training center.

Hales says "there's numerical safety," in that crime stats are down, mostly, except for sexual assault. But he says he wants the numbers to keep going down, "all of them," but that he also wants people to call 911 and "think they'll get justice and fair treatment." One way? Continually changing whom the city hires to work as a cop.

Turner speaks again: Cops who make traffic stops need to tell you why. So people don't think they were stopped just because of their appearance.

Another woman at the panel speaking as a Latina, however, cautions that the reasons officers might give may just be cover for profiling: you're light was out. You swerved in your lane. Etc.

Raiford says "if we felt safe and we were happy with our police force, we wouldn't be here right now."

The speaker is talking to Turner about his through process in becoming a cop after not wanting to do police work initially. "A lot of people don't want to be on the police."

Turner says "we can't close our eyes" to the disconnect. He wants to keep educating people about what cops do. "Maybe we can change it, but maybe we can't," and at least people will understand why those things can't change.

12:39

And now it's time for a lunch break, and a blessing over the room, and the mission hovering over the room, and the meal everyone's about to share.

1:36

The forum has resumed. Turner and Hales have departed—Hales for a meeting, he says, with House Speaker Tina Kotek. He promised to be back for the next meeting, likely next month.

The final few hours are mostly about the Department of Justice settlement agreement. Hales' police policy advisor, Wesson-Mitchell, has mentioned the concern that the deal doesn't address race as strongly as some advocates had hoped it might. It's focused very specifically on findings that Portland police officers have engaged in a pattern or practice of using force against people with mental illness.

She's talking up the promise city hall sees in the agreement for improvements in the bureau's relationship with all communities. Next to her is DeMuniz, the retired Supreme Court justice.

Wesson-Mitchell is also calling attention to a couple of handouts, one from the Citizen Review Committee on crowd control; another from the Independent Police Review on improving how officers track their policing of live music venues, related to the perception cops discriminate against hiphop shows; another on changes to the police bureau's sex assault unit; and another on a recent report urging improvements in how officer-involved shootings will be investigated.

She says all of the hip hop review recommendations have been accepted, that most of the crowd control suggestions seem likely to be accepted, and that most but not all of the shooting investigations have also been accepted.

"I bring these up because we've got committees making recommendations," she says, explaining that the police bureau hasn't yet devised a clean, simple way of tracking and reporting on how it deals with those suggestions.

The hope is the Community Oversight Advisory Board created in the DOJ agreement will improve and guide how all of these myriad recommendations are followed and implemented.

Raiford earlier said she was glad that people filled the room to see Hales and Turner, but that she'd be happier if more people stayed for the legislative, educational nuts and bolts meant to instruct advocates on how they could have their voices heard.

1:46

DeMuniz, the face of the compliance team paid by the city to help oversee police reform, is now introducing himself.

He says the Urban League of Portland plans to help him champion legislation taking "ban the box," a ban on asking people about their criminal past, statewide. He's calling out a "re-entry project" for people leaving prison that he helped start in Marion County, saying it's nearly halved the recidivism rate from the statewide average on 28 percent.

DeMuniz says he's also pitching legislation for people who can't get their court records fully expunged, because of how background search firms have proliferated on the internet, to instead receive a "certificate" of achievement of some kind that they could show employers as a testament to their circumstances having improved.

He's talking about his upbringing in Portland—growing up around NE 72nd, graduating from Madison High, serving in Vietnam, coming home and starting his law career and then moving to the Supreme Court eventually. He was elected by his fellow justices as their chief, a post he held for seven years before retiring.

"I accepted this position as community liaison... because I believe in the power of community," DeMuniz says. His hiring, which is costing the city more money than it otherwise anticipated, was what cinched the selection as compliance officer of a Chicago-based team of academics led by Dennis Rosenbaum and Amy Watson. "This settlement is unique.... It presents a historic opportunity for this city."

1:54

DeMuniz says the community liaison office will operating by the end of the month out at the Rosewood Initiative, near the city's border with Gresham. He'll have an independent website. He's insisted on having COAB meetings filmed and archived, something else the city had little choice but to find more money for.

He's giving his breakdown of the "85-page agreement," which offers prescriptions for changing how officers use force, how officers are trained, how officers track data, and how officers are disciplined. He's citing data collection, improved crisis intervention responses, training changes, and new accountability.

One of the "most important things," is an early intervention system that tracks all potential troublesome conduct an officer might have in their file, so supervisors can see it and head off issues.

"If we do not create sustained change," he says, "we will fail. It will take a bit of time to measure the outcomes here. Ultimately here, one of the goals, these are my words, but we need to create within the police bureau a culture of accountability."

That last part got some applause.

"This is the meat and potatoes we came here for," Raiford says.

2:02

Amy Ruiz, a top Sam Adams' staffer when the DOJ deal was under negotiations, has been hired to work with Hales' office and Commissioner Amanda Fritz's office to help navigate the selection process for the COAB. She's explaining that process, which you can find if you click here. Something like 100 people have applied for the 15 voting positions on the COAB (the police will have five non-voting posts to fill).

A meeting will be planned January 21 to appoint five of the 15, following five nominations by the Portland Commission on Disabilities and Human Rights Commission. The city commissioners will each appoint one of the final five members, to help fill in any gaps. (Commissioner Nick Fish has announced he wants to name Avel Gordly as his choice.

That meeting, attended by 20 or so community groups, will be chaired by State Representative Lew Frederick. The deadline to apply is Friday, January 16—the same day the selection committee led by Frederick meets to determine its selection criteria. The rest of the commissioners are expected to name their choices January 22.

The COAB will have to get working super quickly, setting up several town halls all across the community, among other responsibilities.

2:14

Wesson-Mitchell says the city would like to see more applications from people of color.

"We have to have our voices heard," she says. "We need to be at the table. This is a very, very, powerful table."

She also reiterated something Ruiz said: that this board will require a tremendous commitment of time and energy from its members, several hours a month. Wesson-Mitchell cautioned that the stronger the COAB is, the stronger the city's reform deal with the feds will be.

They've opened things for questions.

Mary Eng has asked why people should trust new Chief Larry O'Dea, who apparently said on OPB that Captain Mark Kruger had some "utility" and that's why he wasn't moving him out of the drugs and vice division. Eng asks about how he'll approach human trafficking victims who may not feel safe because of his perceived ideology.

Wesson-Mitchell says Kruger wasn't ever fired and that he "does a good job" in his role. She says the Drugs and Vice Division will likely change its name to reflect that it doesn't handle prostitution anymore. Human trafficking and prostitution are dealt with in separate issues. She says a staffing study coming out in the next month contemplated realigning some of those units to work more closely together, in one place. Wesson-Mitchell told Eng that Kruger only handles drug investigations now.

2:21

The next speaker, an African American man, asked for the camera to pan around the room to note that the room features too few African American men right now. "If we want change, we're going to have participate in that dialog," he says.

Then he confesses he lives in Vancouver. "I might have to move here to participate in this."

Ruiz points out that "if you work or go to school in Portland, that allows you to be a part of the COAB."

Raiford says "we the people have to be accountable as well," and urges people to seize the opportunity presented by these regular forums, alongside protests, to stand up and speak and learn.

Another speaker is up reading from Daryl Turner's remarks. "Who are they" that Turner's talking about he asks, referring to language many see as blaming protesters for the slayings of two New York officers last year.

"I would let him speak to that," Wesson-Mitchell says.

"He backpedaled," several speakers chime in. There's laughter, even from Wesson-Mitchell, when the Spanish interpreter says she doesn't how to convey the idea of "backpedaled" in Spanish.

Raiford reminds everyone that she called Turner at 1 o'clock in the morning to talk about his statement and that he picked up.

2:27

A speaker asks a bit about the COAB. Wesson-Mitchell says there may be subcommittees for people who want to participate but also want to specialize in certain topics.

"What's the pay?"

There is no pay. But Wesson-Mitchell also raised the possibility of reimbursement for bus fare or mileage.

"So it's love."

Glenn Waco is up saying the absence, relatively speaking, of young black males in the room is "a testament" to the lack of mistrust his friends and peers see when looking at their elected officials. He's coming from a viewing of Selma and says so many of the same issues around fear and doubt persist today.

2:34

Wesson-Mitchell says it's so far cost $5.2 million to begin implementing the DOJ agreement.

"I know people don't trust the police bureau. I totally understand that. But from what's being done so far, it is being implemented," she says of the DOJ deal. "But it needs to be reviewed and evaluated so it can be implemented even better."

DeMuniz spells out that the COCL often referenced in the deal means "compliance officer and community liaison" and says the job of the COCL is to gather and analyze data. That's vastly important, he says. The data will measure compliance.

He calls the settlement agreement "a contract."

"That agreement had to be approved by a federal judge. The remedies exist by virtue of the fact that it's a contract. And the COCL has to appear once a year in front of the federal judge. The history of this country, the integration of our schools the reform of our prisons, have been done by federal judges. I'm not the least bit worried about that part of it. I'm more worried about making sure the data is accurate so that we can truly verify all of the different things that have to occur in this agreement."

He says the goal, again, is making lasting change.

"We can have all the community input in the world. But we have to fashion what we do to have change in the organization, change that's sustainable, so that we can have a culture of accountability."

2:45

"How does this culture of accountability play into this 48-hour rule," a woman asks to applause, referencing terms in the PPA agreement giving cops time between when internal investigators first compel a statement and when the cops have to give that statement. She wants to know if the COAB can change it.

Wesson-Mitchell says that hasn't affected the city's last two shootings. She also says anyone who shoots someone in the community "doesn't have to talk to the police" either.

She says part of the origin of that agreement came from a change in how the grand jury here handles police shootings. Those hearings, several years ago, she says, began being recorded. Cops were then concerned that differences in their initial statements and testimony might be taken out of context and be seen as proof of a lie.

"Officers were perceiving that the media was not going to treat them favorably," Wesson-Mitchell says.

She says it's not delayed investigations getting to IPR or Internal Affairs at the time they need it. It's a bargaining subject, she says. And getting rid of it in union talks in 2017 could mean trading some other policy concession. "That's bargaining," Wesson-Mitchell says.

DeMuniz says the settlement agreement can't impact the union contract (the union was added as a defendant, in fact, and helped tweak the initial agreement between the city and the feds). There could be legislation, though.

He cites the Garrity precedent meant to protect government employees from compelled statements.

"But this cannot help be a subject of this process," he says of reforms and the COAB's role in fostering a discussion.

2:50

The speaker from Vancouver is taking umbrage with something Waco said, about how he wouldn't understand what it's been like growing up in Portland. He says he's worked here for 20 years and has a lot of family here. He says he's marched with Don't Shoot Portland. "I'm very connected with Portland," he says.

"We're all going down, white, black or red, unless we all stand up," he says.

2:59

Wesson-Mitchell says the idea in the next phase of bias training and education in the bureau is to more actively solicit community feedback on how policies and procedures impact people of color or from minority and marginalized communities.

Without that outreach?

"I'm guessing there's a lot of officers or command staff who may not know someone where they can get that information from," she says.

The next speaker says she sees, on the city's website, that the checklist of reforms and their progress shows check marks on several items.

"Where did the police bureau get their input to stop working on stuff?" she says.

"Note that it says 'completed but pending approval,'" Wesson-Mitchell says. "That's the role of the COAB."

She says many of the changes "made sense" so the city didn't wait, after the 2012 agreement, to begin putting them in place. Among them was adding enhanced crisis intervention training as part of an expanded/new behavioral health unit. There's a disconnect because it wasn't until last summer that US District Court Judge Michael Simon finally approved the deal.

That delay came because of discussions on a handful of points—like how use of force would be evaluated, and other issues that may affect the union contract—in contention between the PPA, the feds, and the city.

DeMuniz touts a 2013 book The New World of Police Accountability, which he read over the holidays. It's written by Samuel Walker, a law professor and well-regarded expert from the University of Nebraska. "Information is power," DeMuniz intones. "I found it quite helpful."

3:06

Wesson-Mitchell reminds everyone to check out the section on the cops' website where directives are posted for community review. She also says how important it is for people to file commendations and complaints, so supervisors can know how well... or not... officers are doing.

We seem to be down to the final speaker, after a brief discussion on how people felt about being recorded by livestreamers.

The speaker mentions the training facility that Turner mentioned. "Most of that building" is dedicated to "violence on the part of police on individual citizens." She says she asked about peaceful resolution. She also thought all of the dummies in the training room were black. "Do you think that reinforces" stereotypes, she says she asked an officer.

She says she was told the black dummies don't show dirt... and also that the company that makes dummies mostly offers black ones. That's interesting and maybe ought to be verified.

In any case, thanks to the handful of you who followed along for the past several hours.

"Peace and get out of here," Raiford says. Fine advice.